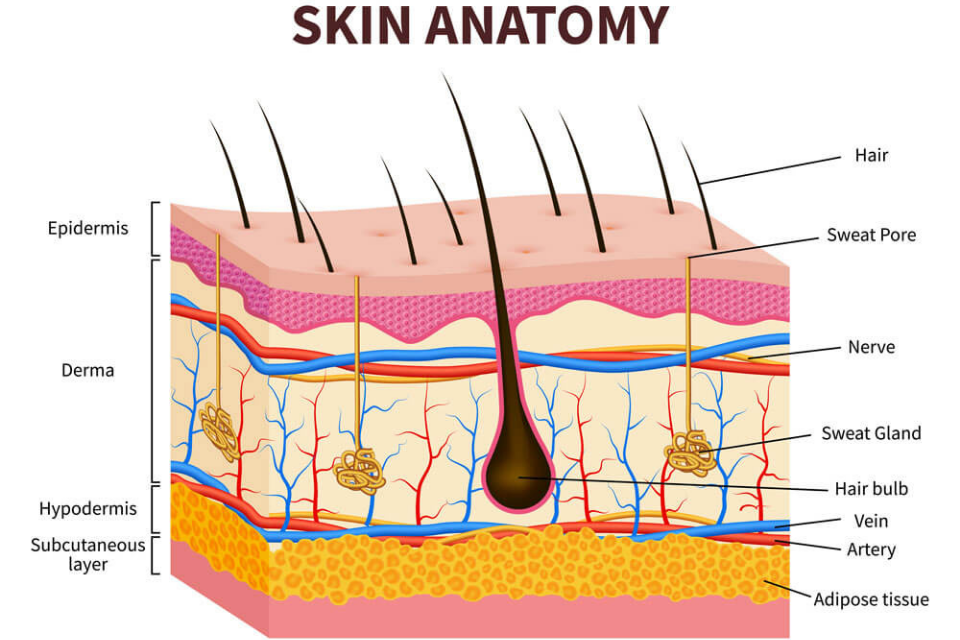

Before we dive into cutaneous pharmacokinetics (PK), methods to quantify API concentrations over time, and develop new concepts, we need to understand the cutaneous anatomy. If you are relatively unfamiliar with cutaneous PK, this will help when I mention specific stratifications, such as the stratum corneum or dermal adipocytes, in future posts. While this will not be an exhaustive explanation of the cutaneous biology, we can begin from the outside stratification and work our way toward the subcutaneous fat. Figure 1 presents a cartoon of the skin’s structure.

Epidermis

The skin can essentially be broken down into three different stratifications. The epidermis (outermost layer), the dermis (the middle), and the hypodermis (or the fat). The epidermis can further be stratified into the stratum corneum and the viable epidermis. For our purpose, this is the distinction that we will use in this post, and subsequent posts, when exploring cutaneous PK.

Stratum Corneum

The stratum corneum (SC) is the major defense against potential xenobiotics. It keeps the good things in and the bad things out. Now, this is a problem because the “bad things” are also our active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that we are trying to get in to the skin.

At the structural level, the cells that are in the SC are called corneocytes, which are no longer living cells. As cells mature and move up from the dermis to the SC they lose their nuclei and develop a cornified envelope instead of a membrane. The structure of the SC is depicted as a “brick and mortar” model where the corneocytes are the brick and the surrounding lipids are the mortar. These corneocytes continuously fall off as cells below them (in the viable epidermis) mature and come to the surface of the skin. While the ‘bricks’ of the SC provide some defense against the penetration of APIs, the ‘mortar’ is actually thought to be the limiting factor; extraction of the lipids or disruption via chemical enhancers often increases the API flux into and through the skin.

Diffusion is the main process in which APIs can get into and through the SC to the deeper layers of the skin. However, this is a fairly inefficient process due to the barrier of the SC. There are several ways that this can be overcome. The two main methodologies are chemical (e.g., penetration enhancers) and mechanical (e.g., puncturing skin with microneedles) methodologies to improve the amount of API that gets to the intended site of action.

Viable epidermis

These are the cells that are deeper in the skin and are termed the viable epidermis as they still have nuclei unlike the SC. These layers consist of the stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and the stratum basal. As these layers mature, there is a keratinisation process that differentiates the cells to create corneocytes.

While it is true that the SC is the major barrier to xenobiotic permeation, the viable epidermis also has metabolic enzymes. These enzymes are similar to ones found within the liver – cytochrome p450. in addition, there is thought to be transporters within the SC/viable epidermis that might also help API permeation to deeper skin layers. There has been research in the area of cutaneous enzymes/transporters similar to what has been extensively characterized in systemic drug delivery with the liver and kidney. However, they are thought to play less of a role in cutaneous API disposition.

Dermis

In addition to the viable epidermis, the dermis is a potential site of action for many topical APIs. This is also the largest portion of the skin at approximately >1 mm thick within a human. Depending on the animal model in use, the dermis can be smaller or larger than the human dermis. The dermis also provides elasticity and strength to the layers above.

The dermis is a densely packed area of tissue with an enormous amount of information. Here, there are hair follicles, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, nerve endings, lymph and blood vessels throughout. As the dermis is highly vascularized in comparison to the more superficial layers within the skin, waste can be removed and nutrients can be delivered to the epidermis. This, of course, also means the removal of APIs that we are trying to deliver to the epidermis/dermis.

Hypodermis

The hypodermis is under the dermis, as the name indicates, and is the subcutaneous fat. While this might not seem all that important, the hypodermis provides protection to the internal organs as there is a cushion from outside forces against the body.

Too Long – I didn’t read

The skin is a remarkable organ that often is overlooked in general but particularly from a drug delivery standpoint as APIs can be delivered both locally and systemic while avoiding unwanted side effects. The stratum corneum is the major barrier to API delivery into the epidermis/dermis. The dermis provides “life” to the stratifications above by delivering nutrients and removing waste.

If you have questions/comments feel free to leave them below! Or if you have a topic you’d like me to write about or expand upon, please let me know!

Excellent explaination Dr. Kuzma. I appreciate your kind contribution helping followers understand the nuances of how to think about skin.

Got any information on how the skins pH presents an added complexity since a diffusion gradient exists which ranges from pH 4.5 to 5.5 and how this might impacts PK study results. (Especially when comparing animal (rat) to human permeation or diseased skin.

Thanks so much no need to respond now but I’m happy to discuss with you further. I still want to develop a collaboration with you soon one day. 😉

LikeLike